Heronless

Sophia Argyris

Palewell Press

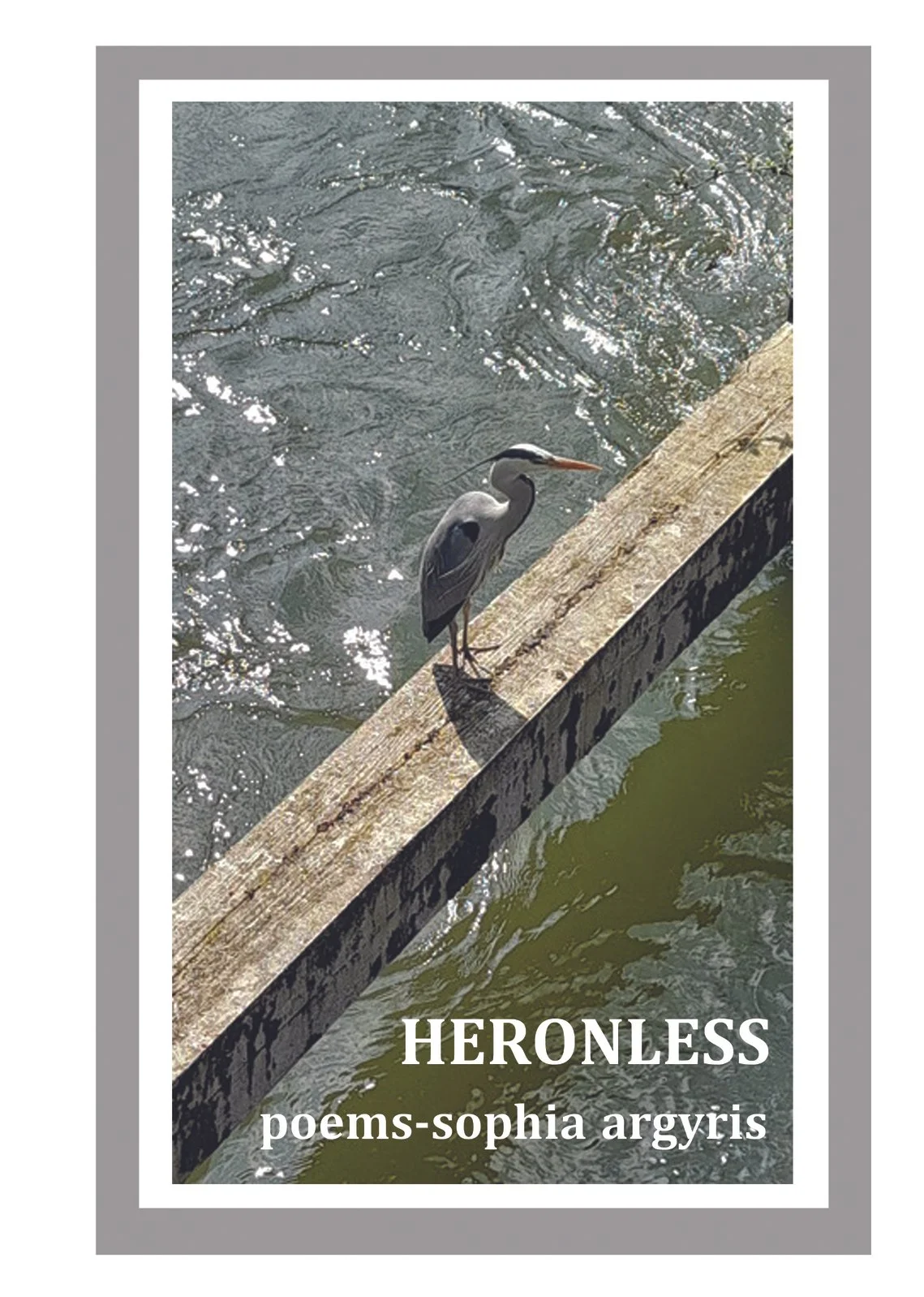

Titles in poetry can be tricky. For many, naming a poem or book is often harder than writing it - myself included. Some titles tell you exactly what the book is about, while others act almost like ‘anti-titles’, pointing to what is not there. When I first picked up Heronless, with its cover showing a photograph of a heron, I expected the latter. I thought it might be one of those playful, ironic titles that actually hides a collection full of herons.

The opening poem, In This Sudden Absence of You, does suggest birdlike ideas, talking of wings and flight, but the pamphlet quickly reveals that Sophia’s poetics stretch far beyond that. Right from the start you can feel her skill with pace. She propels the reader forward with bursts of vivid imagery. We journey through flowers, time, the body and even temperature in some lines and in the next we land in intimate domesticity, perhaps a more literal place. This flitting use of imagery takes the reader from the breadth of the world and what’s in it to very close and personal places in just a few lines, and it’s a skill Sophia uses in a number of poems.

Family is an important presence in these poems, especially her parents, who sometimes appear clearly and at other times seem more distant or harder to reach. Even when the subject matter leans toward absence, the pacing keeps the poems alive. Sophia’s rhythm is key here. Her line breaks never feel like they are slowing us down, but instead they pull the reader onward. Many poems begin in one place and end somewhere completely different, and you often find yourself rereading them just to trace how that journey happened.

There are gentle flirtations with rhyme and sound, but always with a light touch. In contemporary poetry this can be hard to pull off, but Sophia manages it beautifully. Sometimes rhyme appears right in the middle of a line and catches you by surprise, as in Some Sunday with its ‘in a wing shaped bite / a jawing where there should / be flight. The missing…’

The title poem Heronless does not arrive until well into the pamphlet, and even then, the much awaited (for me, anyway) heron never actually appears. This makes the title honest. It is a book about absence, and about the presence that absence can carry.

There is so much more I could say about this collection, but part of its charm lies in discovery. Heronless is full of movement, music and feeling, and it holds its surprises gently.

Sophia was kind enough to answer some questions about her pamphlet...

How did you first get into writing poetry?

I wrote poetry even as a child, I always loved it. As a teenager I wasn’t writing, but I remember being very into Edwin Morgan, Wilfred Owen and Sylvia Plath. I started writing again in my mid 20s. Honestly, I had no idea what I was doing, but somehow a few years later I got a collection (just! It was a few pages over pamphlet length) published by Indigo Dreams. That was in 2014, but still, I always saw myself as someone who wasn’t ‘that kind of poet’, meaning the kind that gets placed in competitions or published by the bigger magazines. And then life got in the way, I was moving from employment to being a self-employed yoga teacher and had to focus on that, so I wrote almost nothing for seven years. I started again after my Mum died in 2022. She was also a writer, and I found a notebook beside her bed that was blank except for a title on the first page. I started writing thoughts in the notebook, and that was the beginning of Heronless.

How did you choose Heronless? Was this always the title, or did it come later?

The title I found in my Mum’s notebook was White Noise and I had some idea I might be able to use that but quickly realised that wouldn’t work for these poems. Initially I planned to call the pamphlet Sudden Absences, and then Oak-Hearted. But in the end Heronless felt right. It has a sense of loss without naming it specifically, and that’s what I wanted.

What role does sound play in your writing process?

I love language, the interplay of sound and meaning. I spoke English and French as a child and speak a small amount of Greek because of my Dad, and I love the connections between words in different languages. I also like the fact some words sound exactly like what they mean, and others absolutely don’t. The Greek word for bill, as in a restaurant bill, always sounds incredibly romantic to me despite the banal meaning.

When I write I try to let the words flow out in a rhythm with some kind of internal partial rhymes or sounds that mirror each other. Then when I edit I ‘bury’ those in the poem a bit so that I usually don’t have definite rhymes at the end of the line but keep some element of the melodic. Having said that I don’t know how well I did that in Heronless.

Was there a poem in the collection that took much longer than the others to get right? What was difficult about it?

Skye never quite felt finished, as if there was more to say. I tried various longer versions, but ultimately decided I liked the unfinished feel better than any of my attempts to elaborate further. I’m still not sure I got Gaia right. I think I was trying to write into something very vast, and I don’t know if I managed to do it justice. The line breaks also could be better. I changed that one so many times and eventually just had to let it be.

What's a line or idea from the pamphlet that you hope readers don't miss?

This is such an interesting question. I had to get my copy and go through it. I turned first to the poems I think of as strongest, and there are lines in those that I could choose, certainly ‘do as little damage as I can’ from the end of Measurements feels important to me in relation to my / our impact on the planet. But I think I might choose ‘As if since birth you didn’t grip / the world like that’ from Unclasp. It pretty much sums up my sense that if we could let go of our grip on our own experience of the world, we could be a lot happier, less attached to and less fearful of much of our lives. This is, of course, also what yoga philosophy and meditation guide us towards. For me it’s still a work very much in progress!

You have another pamphlet due out next year - has your writing changed between them?

I think so. Many of the poems in Blood Tundra started life in Anthony Anaxagorou’s Poetry Room in 2024. I started attending what I think of as ‘The Room’ in late 2023 and it blew my mind wide open, which was exactly what I’d been looking for. I kept feeling myself bumping up against the edges of my own imagination and couldn’t work out how to push into new territory. Those first Poetry Room sessions really helped me with that, letting my mind go a bit wild with imagery or language. Blood Tundra also deals with different subjects, venturing into anxiety and depression, the strange interplay between a desire to be seen and a desire to hide, a little bit of love and a little bit of anger.

Has anyone ever read one of your poems in a way you didn’t expect?

I think every person who has read my work and told me what they liked or thought about it has surprised me. It never ceases to amaze me how poems reach different readers, what they take from it.

What do you do when a poem won't behave?

I try it in various formats. I change the order of lines or stanzas. Sometimes I take two poems that don’t work individually and weave them together to make one poem. I try to be ruthless with cutting lines or phrases that are not elevating the poem. And if nothing works, I put it aside and maybe come back to it a few weeks later to see if I can look at it differently. Feedback from others can also help crack a stubborn poem open. I’m lucky to have a few friends who I swap poems with regularly for feedback. Also, I’ve had some brilliant mentoring over the last two years from both Helen Mort and Anthony Anaxagorou, so I’ve been a bit spoilt.